Title of the exhibition: Samplers 29

April - 31 August 1997

Octagon, Fitzwilliam Museum, Trumpington Street,

Cambridge

Opening times: Tuesday-Saturday 10.00-17.00, Sunday

14.15-17.00, Closed Mondays, admission freeTitle of the book: Samplers

author: Carol Humphrey

Fitzwilliam Museum Handbooks, Cambridge, 1997,

ISBN 0-521-57300-9

Further information from:

Carol Humphrey, Honorary Keeper of Textiles, Fitzwilliam

Museum, Cambridge.

Tel: +44 (0)1223 332 900 Fax: +44 (0)1223 332 923

Fiona Brown, Press Officer, Fitzwilliam Museum,

Cambridge, CB2 1RB

Tel: +44 (0)1223 332 941 Fax: +44 (0)1223 332 923

Press Release.

This exhibition coincides with a new publication in the

Fitzwilliam Museum’s handbook series called

Samplers, which has been written by the Museum’s

Honorary Keeper of Textiles, Carol Humphrey and published

by Cambridge University Press. All the samplers pictured

in the book will be on display.

The Fitzwilliam Museum is fortunate in having received

two major bequests of samplers from collectors with

varying viewpoints and will be exhibiting a selection of

these and others.

Samplers have been worked

wherever embroidery has enjoyed a sustained popularity as

a decorative art, however, it is only in the last 100

years or so that they have been seriously collected.

Almost a third of the Museum’s sampler collection

comes from the bequest of Dr J W L Glaisher FRS - better

known for his collecting of pottery and porcelain - and

another significant portion from the bequest of Mrs

Longman.

Dr Glaisher’s collection, received

by the Musem in 1928 was collected mainly at a time when

samplers were not widely sought and it is clear that he

intended to collate a comprehensive, dated selection of

examples from the seventeenth century. The result was a

wealth of dated samplers giving sound chronological

evidence of the changing style, including one piece

dating from 1629 which was the earliest known dated

example until 1960, when the Victoria and Albert Museum

purchased a sampler by Jane Bostocke from 1598.

Mrs Longman’s bequest supplemented

Dr Glaisher’s collection and widened its scope. She

was part of the publishing family and there is evidence

from her letters that she asked her well-travelled

friends and relatives to look out for possible additions

to her collection on their trips abroad. In this way she

managed to acquire a number of continental examples and a

more cosmopolitan (if less focussed) collection than Dr

Glaisher’s.

The combination of these

two bequests, plus the addition of a number of English

and Continental samplers over the years has resulted in a

range unusual in a single collection. The Museum’s

collection therefore represents an important holding in

the history of this particular art form.

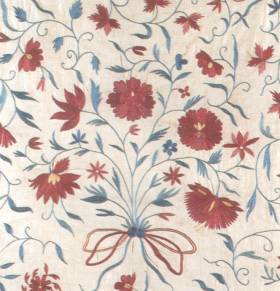

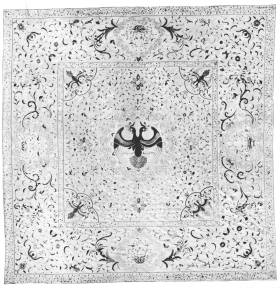

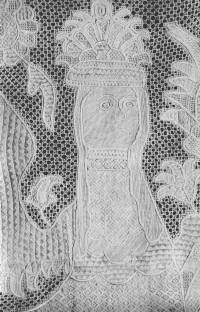

| This

catalogue (see Newsletter No 5, p.8) shows 2

examples of pulled threadwork. One in combination

with hollie point, and the other one of a later

period, 1830 Whitework Sampler:

T.139-1938, 22 x 24,5cm

English, 1719, March 13, 1719 / Iohanna SPeRINCK.

Linen. Embroidered with linen and silk threads in

buttonhole and chain stitch with pulled thread

work and hollie point fillings.

Hollie point is very english. It was a popular

trimming or insertion for infants’ clothing

and christening sets but was not adopted in

Europe. It is suggested that the sampler was

worked by a young woman whose family had settled

in England or one who has come from the continent

to work as a governess.

|

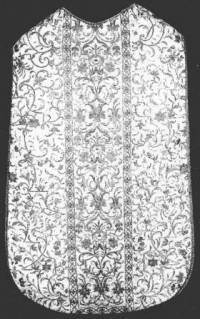

| Whitework

Sampler T. 4-1939, 12 x 30,25cm, German or

Danish, 1853, Initials F.J. R.Z., Cotton.

Embroidered with white cotton in chain stitch,

with panels of pulled work. With the return of

more elaborate styles in the 1830s, the more

complex whitework techniques enjoyed a revival

and were again in demand for their traditional

purposes. The needlewomen display similar levels

of expertise, even if the style of work is

separated by decades of changing taste. |

English,

March 13, 1719 / Iohanna SPeRINCK

|

|

|