B

B E

E D

D| ANNE WANNER'S Textiles in History / books |

| The

Embroideries at Hardwick Hall, by Santina M.

Levey, National Trust books 2007, 400 color photographs,

280 x 219 mm, 400 pages, ISBN 13: 978 190 5400 515, £ 50.- Available from selected Trust shops, good bookshops, or from the distributor (+0870 787 1613) http://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/main/w-abc4.pdf Text copyright by Santina Levey Photography copyright by NTPL/Brenda Norrish (NTPL = National Trust Photo Library) Linedrawings copyright by The National Trust/Avril Hart, excepte where credited otherwise next to image and on pp. 271, 272 where artwork by Fetherstonhaugh Associates. |

| see also the first book by

Santina M. Levey: An Elizabethan Inheritance, The Hardwick Hall Textiles by Santina M. Levey, London 1998, ISBN 0 7078 0249 0 112 pages, 100 pictures most of them in colour Contents: Introduction, 1) before the building of the New Hall, 2) Hardwick New Hall and the 1601 inventory, 3) Embroidery, needlework and other techniques, 4) the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, 5) the 6th Duke and beyond. Notes, Bibliography, Appendix, Glossary, Index |

| content: The book is divided into 2 parts: Part One: provides background information about the Countess and a context for the textiles with which she furnished her house. Part Two: comprises the formal catalogue, organised by technique into three main sections: Embroidery, Needlework and Wrought Linen. There is also a brief section on Turkey-work and an appendix devoted to a rare Indian coverlet. |

Part

Two: The Catalogue: |

- Room Valances - Long Cushions - Square Cushions - Miscellaneous Pieces - applied Needlework Section 3: Wrought Linen - Table Linen - Bed Linen - coloured Cutwork and Related Pieces Section 4: Turkey-Work |

| The catalogue itself is

divided by technique and, within each section, by type of

object. Santina Levey looks at each piece in turn,

explaining how it was made and by which type of

embroiderer. Many of the items are well documented, and Levey throws new light on the ways in which they are displayed and even re-used at different times. She also provides fascinating new material on design sources. . |

The pieces range from

small panels of needlework and linen sewn with gold and

coloured silks to a dramatic set of huge wall

hangings depicting "Heroic women of the Ancient

World". Most of the pieces were, made within her household and have subsequently remained in the charge of the Dukes of Devonshire for over 400 years. |

For the following book

review, besides of the images, also some parts of the

text are reproduced. These parts are marked with the

respective pages in parenteses. |

| Background The purpose of the first part of the Catalogue is to provide a context for the objects described in Part Two: - To what extent are they typical of their day? - What do they illustrate in terms of subject matter and design? - Where did the ideas and images come from? - Since most pieces were produced within the household, who made them and how was the work organised? - Finally, what do the answers tell us about Elizabeth Hardwick, and how do they fit with existing perceptions other? |

The majority of the catalogued items are now housed in the New Hall at Hardwick. Included are the Oxburgh Hangings, which are divided between Oxburgh Hall in Norfolk and the Victoria and Albert Museum London. The textiles were specifically made to furnish the house, owned by Elizabeth, Countess of Shrewsbury (1527-1608). They represent a tiny proportion of the textile furnishings listed in the 1601 Inventories of her three houses - Chatsworth and the Old and New hall at Hardwick. They are supported by a large quantity of archival material. This includes several household account books and a series of inventories. |

She was born Elizabeth Hardwick at Hardwick Old Hall in 1527, and after a childhood marriage to William Barley, who died within two years, she subsequently married Sir William Cavendish (1547), Sir William St Loe (1559) and George Talbot, 6th Earl of Shrewsbury (1567), by which marriage she became Elizabeth, Countess of Shrewsbury. It is worth emphasising that from the time of her marriage to Sir William Cavendish the future Countess was in touch with professional embroiderers. Sir William knew Henry VIII s embroiderer, William Ibgrave, through his official duties. (see pages: 9, 13) |

| In an introductory chapter

the development of English Embroidery is

shortly outlined. There is a remark on "Opus

anglicanum", famous from the 13th c. to the mid-14th

c. With its costly material it became a luxury craft,

often linked with that of the goldsmiths. With Tudor

dynasty there was an increase in wealth as international

trade developed, and it was a favourable time for

embroidery, the reigns of Henry VII (1485-1509) and Henry

VIII (1509-1547) were fruitful. During the first half of

the later's reign there were 2 embroideres to the king,

by the end there was one only. And the all-male Broderes

Company was granted its Royal Charter by Elizabeth in

1562. (see page 39) |

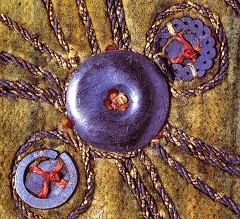

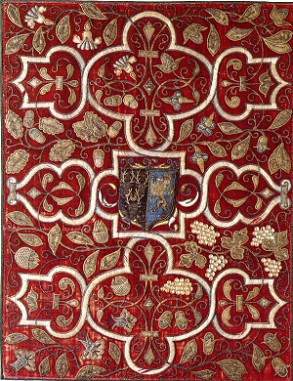

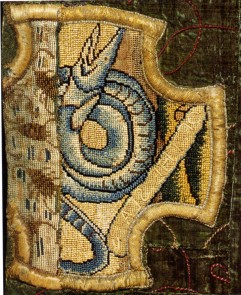

Material: The

skill of the professional male embroiderer lay in the

manipulation of metal threads and in the

combination of rich materials with expensive threads. It is known that Lady Cavendish bought for her embroiderer large quantities of gold and silver thread, together with yellow and white floss to couch dit down. The metal threads, of a type now called file, were made of thin metal strips round a core of floss silk. Those used on the Hardwick embroideries consist of two shades of gold. Four main techniques are employed: the plied threads are invisibly couched, the silk thread being hidden in a twist of the metal thread and visible on the back as a neat line of stem stitches; all the flat- laid triple or paired file are visibly couched with complementary but contrasting floss (B); to cover a narrow area, usually padded with thick linen threads, a single line of file is taken from |

side to side of the motif,

and held by a single stitch; for larger areas, the file

is similarly laid to and fro, but is visibly couched, in

a variety of decorative patterns Another form of metal thread used extensively on the Hardwick embroideries, although mostly in small pieces, is purl. This is made of solid metal wire or strip coiled like a tiny spring. There are four types: a fine coiled wire often pulled out and twisted with floss (C); a narrow strip (2mm wide) forming a smooth round tube (E); a narrow strip (2mm wide) less tightly coiled, forming an angular profil, and a heavier, wider strip (3mm wide) loosely coiled to show the floss core, often of mixed or mingled, colours (D); heavy strip (2mm wide) was used flat, or corrugated and couched with coloured floss across the indentations. (see page 51) |

B B |

E E |

D D |

F FMetal ornaments included three sizes of domed spangles with diameters from 4mm to 1cm; posy-rings of two loosely twisted thick wires, subequently flattened, which are of two sizes, with diameters of roughly 1cm and 5mm, as are split rings of thick, flattened wire; their centres were often filled by square off-cuts of metal strip, held down by floss since they had no central hole (F).  C C |

H HAlso found are small stamped-out spangles with raised rims, 3-4mm in diameter; flat, pear-shaped spangles, approx. 6mm by 4mm (H) ; figures-of-eight spangles of thick flattened wire, 5mm high, and flower heads stamped out of thin metal sheet and slightly moulded, 3mm x 4mm (I). Plus tiny metal tubes of rolled-up discs or strips of metal, 0.5mm to 1cm long, 2mm in diameter;  I I |

K Ktiny ring-like metal beads, 1.5mm in diameter (K); and thick wire wrapped with thin wire, preseumably of a contrasting colour and twisted into various shapes (L). (see page 52)  L L |

| The general increase in

wealth during the sixteenth century saw a growth in

personal possessions. In addition, a degree of comfort

was introduced, with padded seat furniture that may have stimulated the increasing popularity of the hard-wearing techniques of needlework and Turkey-work. En suite furnishings were recorded at Chatsworth as early as 1553, and a new profession was emerging of furnisher/finisher/upholster, who combined manual skills with something of the role of an interior designer. (see page 23) The fabric to be embroidered was mounted in a frame and carefully prepared with the design drawn on the surface; by the later sixteenth century it was possible to buy such prepared fabrics. Among the stock of a Newcastle merchant, Ralph Cole, there was in May 1565, "A drawen cloth to be sewed vij.s".(see page 24) |

The first English

book with designs specifically intended for embroidery

was Thomas Geminus's Morysse and Damashin renewed and

encreased very profitable for Goldsmythes and Embroderars

of 1548. There was also a long-established relationship between embroiderers and painters, which is described by the early fifteenth-century painter, Cennino d'Andrea Cennini in his II Libra dell'Arte (A Handbook for Painters), one section of which deals with painting on fabric, including drawing for embroiderers, and there are many examples of the sharing of patterns and pooling of skills between craftsmen. (see page 24) |

Although the Countess is

likely to have had her own ideas concerning the subject

matter of her furnishings, their translation into objects

depended on the availability of a draftsman, probably a

painter, although other workmen often had the necessary

skill, and also of an appropriate printed image on which

a working design might be based. (see page 25) For most of the sixteenth century, wall hangings were an important means of reducing draughts and conserving heat, while adding colour and pattern to an interior; they were also moveable. Most hangings were textile-based although they were divided into several overlapping categories, which reflected their owners wealth and social standing. (see page 26) |

|

|

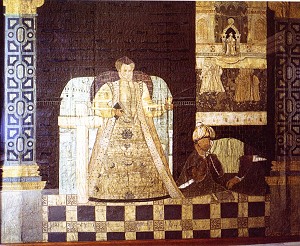

Wall and Bed

Hangings (1A-E) 1A: Arthemesia flanced by Constans and Pietas figure of Arthemesia: 120cm. Design source: The countess probably knew about classical architecture and design via a network of collectors and builders who owned books and prints. John Shute's First and Chief Grounds of Architecturee of 1563 may have influenced the architectural frame as well as the personifications. Whoever worked out the details of the design and drew it out, was a skilled drauthtsmann, with a well-grounded knowledge of classical architecture. (see page 63) She commissioned dramatic wall hangings based on classical architecture, with carefully chosen historical women and personifications to express her personal code of conduct. (see page 386) |

|

|

2C: Hanging

depicting Faith and Mahomet (85,8 cm) and the engraving: Faith and Mahomet from the set of Virtues and their Contrary Vices, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam. (see pages 100, 101) |

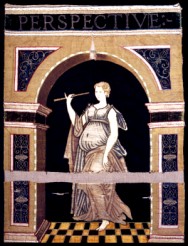

Wall and Bed

Hangings: Set of eight panels depicting the

Liberal Arts: Astrologie, Perspective, Logique, Musique,

Architectura, Arithmetique, Grammatica and Rethorica (see

page 116) Perspective (figure 42.5 cm) |

Wall and Bed

Hangings: Set of 42 panels (from a once larger

set) with portals containing Small Personifications (see

page 138): Justicia (panel 30 x 30 cm) |

Engraving of eight Virtues, workshop of Virgil Solis, Albertina, Vienna (see page 139) |

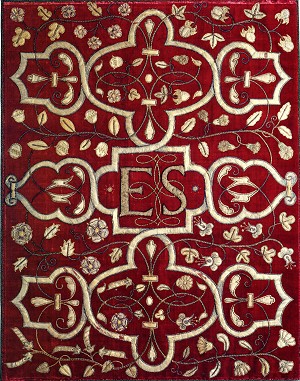

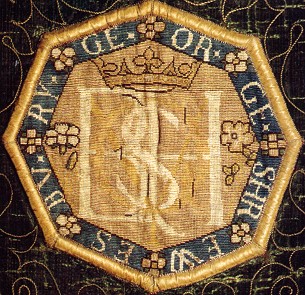

Panel with the

initials E S for Elizabeth, Countess of Shrewsbury

(68,3 x 53 cm) (see page 183) |

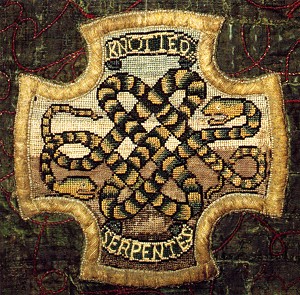

Panel with the arms

of Cavendish impaling Talbot, for and Henry Cavendish

and Grace Talbot (see page 186) |

Room Valances It was not uncommon in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries for rooms hung with relatively simple woven or embroidered fabric to have a valance running round the room, much as later papered walls had a deep upper border or frieze. (see page 29) Heraldry |

| Needlework

depends on a balanced plain-weave ground, which provides

an easily followed grid for the counted-thread stitches.

The plain-weave linens used in the sixteenth century were

neither as regular nor as rigid as modern canvas,

however, and none was woven like the Penelope canvas with

paired threads. (see page 270 The linen-canvas grounds, whether a small square for a single slip, or large enough for a table carpet, would have been stretched in an embroidery frame. In most inventories these are called 'tents'. The term 'tent' probably goes back, like the tenter-hooks used in stretching and straightening cloth, to Middle English and the Medieval Latin tentorium (stretch), rather than to the French tenter from the same root. (see page 270) |

Needlework furnishings make up a substantial part of the Hardwick Collection. It is one of the few areas in which it resembles most museum and private collections, and for many people the term 'Elizabethan embroidery' is synonymous with applied needlework -slips on grounds of velvet, silk or wool, of which a substantial quantity survives. Needlework is a tough technique, its high survival rate does not reflect its relative importance vis-a-vis other techniques in the sixteenth century; by then, however, the terms needlework and embroidery were beginning to be applied with greater precision, and the two techniques were recognised as the preserves of distinct groups of professional workers. In England both had their roots in practices of the medieval period when England was internationally renowned for its Opus Anglicanum (English work). (see page 268) | The only pieces of

needlework that can be linked to particular people are

those worked by Mary Queen of Scots and the

Countess herself, together with their attendants.

But it can be deduced that several other items are the work of casually employed journeymen embroiderers, as well as domestic servants and attendants, both male and female. Only in a few cases does the quality of the work suggest either the presence of a master embroiderer (male or female) or that the object had been purchased, probably in London, from a professional workshop. (see page 270) |

Table carpet with a

central scene of the Judgment of Paris, dated 1574

(80x117 cm) (see page 274) |

Detail of the lower

grotesque mask in the centre of the Judgment of Paris table carpet  The source: engraved cartouche by Pieter van der Heyden, after Jacob Floris, published in Compertimentorum quod vocant multipex genus, Antwerp, 1566) (see page 273) |

Table and Cupboard Carpets In the sixteenth century a major contribution to the colourful interiors of a well-furnished house was made by the textile coverings on tables and open-shelved cupboards where, on important occasions, they were combined with arrangements of gold and silver plate in a visible display of wealth. (see page 30) |

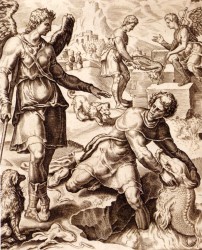

Dammaged table

carpet with the arms of Talbot impaling Hardwick: scenes

from the story of Tobit, dated 1579 (see page 280) The angel instructs Tobit to catch a giant fish and do cut out its heart, liver and gall bladder |

Angel and Tobis from a set of engravings after designs by Maarten van Heemskerck, published in Antwerp by Hieronymous Cock in 1556 (Trustees of the British Museum) (see page 280) |

Cushions played an important role in sixteenth-century interiors and their presence in an inventory - their number and quality - is a good indicator of the wealth and status of the owner. The absolute minimum was one for the great chair in the Hall but, in royal palaces and great houses, they might total a hundred or more; there were 92 in the New Hall at Hardwick and a further 50 in the two older houses. The cushions came in different sizes and served different purposes; they also responded in their design and use to changing concepts of comfort and display. (see page 30) |

Long cushion: the

Judgement of Solomon "an other long quition of nedleworke, silke & Cruell of the stone of the Judgment of Salomon [sic] betwene the too women for the Childe, with frenge and tassells of blewe silk and lyned with blue damask" (1601 Inventory: on a window ledge in the Gallery) H. 59.5cm (23 3/8 in). W. 133cm (52 3/8 in). Size of central scene: 46cm x 12cm (18 3/8 x 47 3/8 inches) (see page 312) |

|

Two cushions are recorded in the 1601 Inventory but were not made within the household; whether given to the Countess, or purchased by her, they are the product of a professional workshop. No direct source for the whole scene has been identified, nor is it likely to be, but the cushion provides a good example of how a designer might use an available image as a starting point. The closest here is a woodcut by Jost Amman in his Biblia Sacra of 1564. (see page 312) |

| The cusions in question demonstrate how effective canvas-work can be when an accomplished under-drawing is put into the hands of a skilled worker. There is no doubt that these cushions are professionally made but whether in London or on the Continent is not clear; they depict figures dressed in the fashions of the French Court and some of the design sources are, or are based on, French prints; but these were also available in | England, together with

craftsmen and women capable of working to this standard.

There is little on which to base a decision except

perhaps the border pattern of naturalistic flowers and

little birds. Despite the differences in scale and technique, this bears some resemblance to the borders on the Judgement of Paris Table Carpet, as well as to borders on English needlework of the seventeenth century. |

There are no directly comparable sixteenth-century examples in England, Flanders or France, and it would be helpful to know if the inventory clerks responsible for listing the Earl of Leicester's four 'longe cushions of french nedleworke' in 1588 had prior knowledge of their origins, or could recognise them as French by details now lost to us. ( see page 312) |

|

|

|

| The Oxburgh Hangings

now comprise three partly reformed and heavily

repaired hangings, a valance made from joined pieces cut

from another hanging, as were a further 27 loose pieces,

including a fourth central square. The latter are now in

the V&A and the hangings and valance are at Oxburgh. It is not in doubt that the needlework panels on the hangings are those on which the Queen of Scots, the Countess and their attendants began work almost immediately after Mary was placed in the charge of the Earl of Shrewsbury in January 1568/9. Their production was well suited to the peripatetic life of the Queen, which during the next two years saw her moved to and fro between Tutbury,Wingfield Manor, Coventry, then back to Tutbury, Sheffield and Chatsworth, before returning to Sheffield Manor in December 1570, where she was to remain for most of the following fourteen years, with short breaks at Buxton,Worksop and Chatsworth. |

There are related panels

still at Hardwick, and it has been suggested that those

on the Oxburgh Hangings had also remained as part of a

substantial collection of unused pieces. That this cannot be the case is made clear by the materials and techniques used in their mounting, which link them to the now dismembered set of Small Heraldic Panels. The Oxburgh Hangings will not be fully catalogued since they are not part of the Hardwick Collection and have been the subject of in-depth studies by de Zulueta (1923) and Swain (1973), as well as attracting attention from such other specialists as Jourdain (1910), Nevinson (1936, 1976) and Digby (1963). (see pages 339, 340) |

|

| Summary and

Conclusions. Hardwick was not subjected to the constant refurbishments imposed on Chatsworth and for much of the 150 years following the Countess's death, the state apartments and fine chambers on the upper floors remained relatively undisturbed. The moveable items were packed away until disturbed by the 4th Duke's alterations in the mid eighteenth century. Most of the surviving pieces were

in the state apartments at Hardwick or in the Countess's

own rooms on the floor below. They need to be studied in

the context of both the three 1601 Inventories and the

earlier ones of Northaw (c.1550) and Chatsworth (1553 and

c.1566), which together provide information about

attitudes to textile furnishings, particularly to the

lasting value of costly pieces. |

Born in 1527, the future

Countess had absorbed from her mother and aunt ideas of

house management rooted in the late medieval world and,

although she was to absorb many new concepts before her

death in 1608, at core she remained wedded to older

values. She was responsible for household furnishings

from her marriage to Sir William Cavendish in 1547 until

her death, and it is this fifty-year span of supervision

during a period of substantial change that makes the

Hardwick collection so important. As Lady Cavendish, she

had employed embroiderers, seamstresses and lace makers,

and after her years in close contact with the court, she

knew what she wanted. Intimations of mortality may have prompted the Countess's move into her unfinished New Hall in October 1597, and it was not entirely finished when the Inventory was taken in January 1601 to accompany the will that she signed in April. |

She commissioned dramatic

wall hangings based on classical architecture, with

carefully chosen historical women and personifications to

express her personal code of conduct. But she also

retained a liking for older styles, represented by her

needlework table carpets, for example, with their fleshy

fruit and foliage. That all the furnishings were not in place is clear from the still-unpacked trunks in the Countess's private quarters, and by the duplication of table carpets and wall hangings for some of the state rooms. Not all the pieces fitted easily into their allotted spaces. The second set of hangings was probably not finished until after the move to the Old Hall. We know from later descriptions that the 'patchwork hangings' were on three sides of the room and it is possible to suggest how they were fitted in. (see page 386) |

| This informative

list is published in the book on page 396; it is reproduced here because these sources of design in 16th and 17th c. may be helpful for museums and collectors in classifying similar embroideries of this time Sources and influences A list of books and visual sources that were known to Elizabeth, Countess of Shrewsbury, her immediate family and acquaintances, including Mary Queen of Scots. Books at the Countess's bedside: Calvin, John, Sermons Upon the Book of Job C.S. A Brife Resolution of a Right Religion A 'booke of meditations' A commentary on Solomon's proverbs Two untitled books Book recorded by her at Northaw: Chaucer, Geoffrey, The Complete Works Books known to her elsewhere: Aesop's Fables Castiglione, Baldassare, The Courtier (1528), transl. Thomas Hoby (1561), ms. copy of book III Cicero, Marcus Tullius, De Inventione; Offices Dee, John, by word of mouth and his translations of other works Elyot, Sir Thomas, A Boke Named The Governor (1531) Erasmus, Desiderius, Adages Euclid, The Elements of Geometric, transl. Henry Billingsley (1570) More, Sir Thomas, Utopia (1516) Ovid, Metamorphoses Spenser, Edmund, The Shepheardes Calender (1579) Virgil, Eclogues Whitney, Geffrey, A Choice of Emblems (1586) |

Visual sources known

to have influenced the Countess's embroidery, needlework and houses: - Aldergrave, Heinrich (c. 1483-1555), engraved figure of Rhea Silva, probable source for Lucrecia - Amman, Jost, Biblia Sacra, Nuremberg (1564) - Collaert, Hans, Virtues and Their Contrary Vices after Crispijn van den Broeck?, Antwerp (1576) - Delaune, Etienne, set of figures of the Liberal Arts - Faerno, Gabriel, Centum Fabulae ex antiques auctoribus (1573) - Floris, Cornelis, prolific designer of grotesque ornament, including the mask on the Lucrecia Hanging, engraved by Frans Huys (1555) - Floris, Frans, his designs engraved and published by Cornelis Cort: - sets of the Virtues (1555); The Cycle of the Vicissitudes of Human Affairs (1561); Pastoral Nymphs and Goddesses (1564) - Floris, Jacob, Compertimentorum quad vacant multiplex genus, engraved by Pieter van Heyden, Antwerp (1566) - Gesner, Conrad, Icones Animalium (1553); Icones Animalium Aquatilum (1560); Icones Avium (1556) - Heemskerck, Maarten van, scenes of the story of Tobit from the Apocrypha, pub. by Hieronymous Cock (1556); Parable of the Prodigal Son, pub. by Philips Galle (1562) - Hopfer, Daniel, engraved plate of ten grotesque friezes, Augsburg (1532) - Hopfer, Hieronymous, figure of Fortitude, reversed image of design by Marcantonio Raimondi - Serlio, Sebastiano, Tutte le Opere d'Architettwa et Perspectiva - Shute, John, The First and Chief Grounds of Architecture ..., London (1563) - Solis, Virgil, and Workshop of, single woodcut of Eight Virtues, Eight Virtues in Landscapes, Eight Virtues in Clouds, reversed image of Rape of Europa after Bernard Salomon (1563), misc. images of animals, birds and plants - Stradanus, Johannes, The Return from a Bird Hunt, from a set of engravings of Hunting Parties published by Philips Galle (1578) - Vos, Maarten de, The Element of Air, pub. by Gerard de Jode (c.1582) - Vredeman de Vries, Jan, Grottesco in diversche manieren (1565); Caryatidum ...sive Athlantidum (1565); and others |

| home content | Last revised 14 November, 2008 |