| |

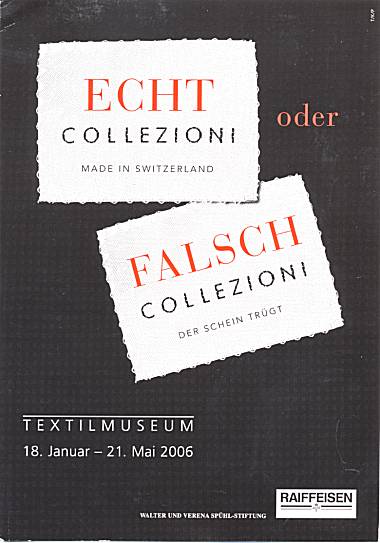

Fakes

in the 15th century

Eastern Swiss textile manufacturers

expanded their commercial interests beyond the national

borders at an early stage. In the 15th century, St.Gallen

linen was sold throughout Europe and from Morocco to

Syria and Persia. Part of the "white gold's"

success was quality assurance. The good fabrics received

were marked with "G", a quality seal recognised

in all the markets. Old documents evince, however, that

such seals were no protection against fakes. In 1477, for

example, an Arbon merchant was exposed who offered linen

fabrics marked with a faked "G" at a Frankfurt

trade fair.

French products from Eastern Switzerland

From the second half of the 18th century onwards,

Eastern Swiss women started to embroider muslin, with

Appenzell women proving particularly skilful. French

companies from Paris and Nancy sent fabrics on which

patterns had been printed to the Appenzellerland to be

embroidered there. In the 1830s, the Appenzell embroidery

firms emancipated themselves and designed their own

patterns. Even so, France still sold Appenzell

embroideries as its own products as late as the World

Exhibition of 1889.

"Hamburghs" from St. Gallen in North America

In 1853, a Hamburg businessman purchased a large

volume of machine embroideries in St.Gallen for a New

York company. In the US, he sold them as

"Hamburghs" in order to deceive his competitors

about the actual source of these new articles. It was not

long, however, before North American customers bought

their goods directly in St.Gallen.

Industrial espionage

he city of Plauen in Saxony carried out industrial

espionage in 1857 by moving a hand-embroidery machine

from St.Gallen to Plauen and wooed the necessary

mechanics and embroiderers away from St.Gallen.

On the look-out for better earnings, Eastern Swiss

embroiderers and their families moved to St. Quentin

(Department of Aisne, France) in the late 19th century.

Both Plauen and St. Quentin became St.Gallen's

competitors

St. Gallen embroidery from Plauen

Imitations of genuine lace

The development of machine-produced embroideries was

perfected on a constant basis. Only experts remained able

to distinguish between high-quality machine embroidery

and hand embroidery.

For resourceful St.Gallen businessmen, the invention of

burnt-out embroidery in 1883 opened up broad new horizons

for the embroidered imitation of hand-made lace. The

so-called "St.Gallen lace" would earn world

renown.

In the 19th century, Switzerland had textile finishing

agreements with various countries. This meant that

fabrics could be embroidered, or the embroideries on them

completed, in other countries more or less without

payment of customs duties. Thus, in times of great

demand, St.Gallen companies had part of their products

finished in the Austrian Vorarlberg or in Saxon Plauen.

Conversely, they finished woollen fabrics for English

companies. France did not permit any finishing trade,

which prompted St.Gallen firms to operate embroidery

machines in France.

Product piracy – more topical than ever

The big issue for the embroidery industry has always

been the imitation of patterns. Newly designed patterns

provided no guarantee that the general public would like

them. The imitators of embroideries were able to wait for

the most popular patterns without making large-scale

investments in new designs, and pattern pirates increased

their profits by reducing the number of stitches and by

using cheaper materials.

Ten to fifteen years ago, digital technology made it

possible for patterns to be copied a short time after the

presentation of the latest collections. Clothes

manufacturers were thus able to have their fabrics

produced at low cost without having to order the

expensive originals from Swiss companies.

In more recent years, it has not only been the patterns

that have been copied, but even finished products such as

entire garments or accessories. The losses that such

fakes generate for the Swiss textile industry run into

millions of francs

Ursula Karbacher, lic. phil. I, Curator |